When I first heard about giving a Christmas recital with the Huntington Women’s Choir, these ideas for songs crossed my mind: “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer,” “Jingle Bells,” and “The Little Drummer Boy.” Thankfully, the Women’s choir would not sing any of these selections. Instead, we were handed a copy of “Hear the Sledges with the Bells.”

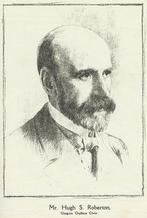

This unaccompanied song for first and second soprano and alto is written by Hugh S. Roberton. And to everyone’s surprise, the song is adapted from a poem by Edgar Allen Poe titled, “The Bells.”

During the Huntington Women’s Choir holiday recital, the instructor, Judy, confidently claimed, “it was perhaps the only happy moment in Poe’s life.”

Naturally, listeners concurred with this thought as the singers recited, Hear the Sledges with the bells, silver bells… What a world of merriment their melody foretells… how they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle, tinkle in the icy air of night… While the stars that over sprinkle, all the heavens seem to twinkle with a crystalline delight.[1] However, scholars and researchers argue the poem’s jubilent appearance.

Naturally, listeners concurred with this thought as the singers recited, Hear the Sledges with the bells, silver bells… What a world of merriment their melody foretells… how they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle, tinkle in the icy air of night… While the stars that over sprinkle, all the heavens seem to twinkle with a crystalline delight.[1] However, scholars and researchers argue the poem’s jubilent appearance.

Kenneth Silverman in his book, Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending  Remembrance, claims the ringing of the bells are symbolic of the changing seasons: the transition from spring into winter. Silverman claims Poe may have used the ringing of the bells as a metaphor for life itself.[2]

Remembrance, claims the ringing of the bells are symbolic of the changing seasons: the transition from spring into winter. Silverman claims Poe may have used the ringing of the bells as a metaphor for life itself.[2]

The Edgar Allen Poe Society of Baltimore offers an opposing view to Silverman’s interpretation. According to their historical records, Poe had no inspiration for this poem. He was staying at his cottage in Fordham, New York, and while with Marie Louise Shew- his wife’s nurse- in the same room; he listened to her comment on the bells ringing from afar.[3]

Whether or not Roberton interpreted “The Bells” as a dreary and grim rhyme, he certainly didn’t express it in his musical composition. Aside from the many interpretations and analysis created around this poem, Roberton wrote his song with a vivacious tempo and in the meter of 2/4, a meter used repeatedly for tunes within musicals. The key signature of D flat major, a key recognized by the tradition of romantic music as whimsical and dreamy, is another component that pulls the initial tone of the poem into a different direction.

“Hear the Sledges with the Bells” is a delightful song that invokes holiday cheer and joy without taking part in the fabricated repertoire fed to consumers Christmas after Christmas.

[2, 3] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. “The Bells,” (December 4, 2010), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bells (accessed December 12, 2010)