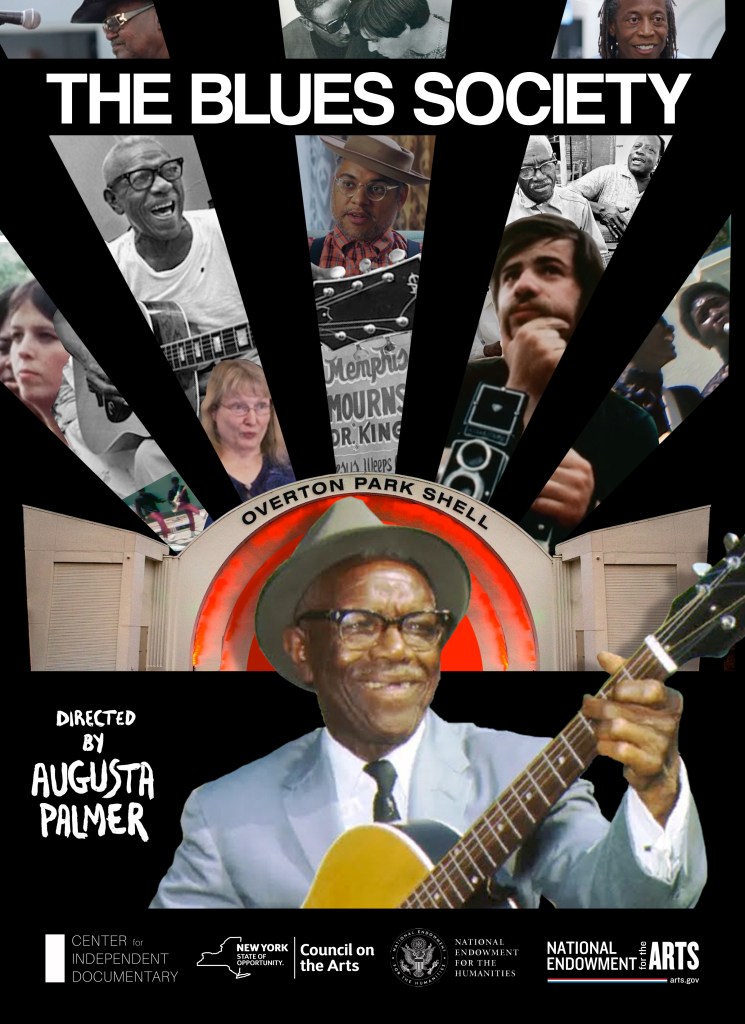

Watching The Blues Society, the documentary film directed by Dr. Augusta Palmer, inside the Firehouse DCTV theater as part of a select screening, I learned many new lessons about the blues. The first involves the motivation behind the founding trio, Nancy Jeffries, Robert Palmer (who was Dr. Palmer’s father), and Bill Barth’s, need to start The Blues Society: archiving blues music did not stem from an interest in preserving sounds of the past; it came from recording sounds of the present. During the 1960s, especially in southern cities like Memphis, Tennessee, white and black Americans were prohibited from congregating (The Blues Society).

In Dr. Palmer’s film, Memphis-based filmmaker and writer, Jamey Hatley, says, “That’s what you heard every Saturday, all day Saturday. The blues, to me, it was entrenched into [a] kind of community.”

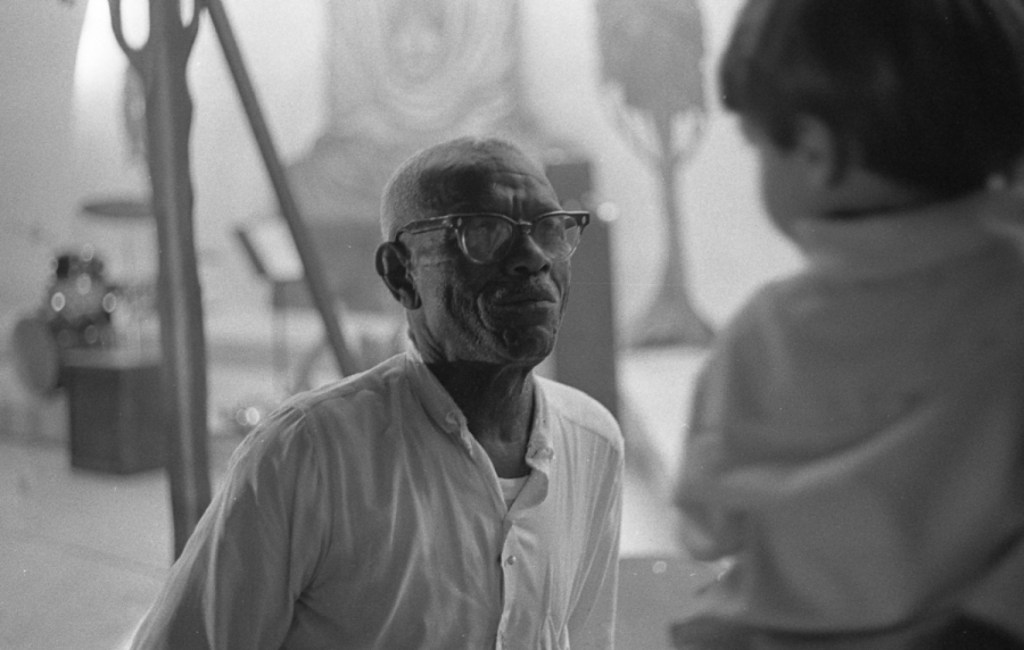

The film shows rare clips of musicians, such as Furry Lewis, playing blues guitar in a crowded room of black and white folks. Following that, an interview with the owner of The Bitter Lemon Café, John McIntire, exhibits that many establishments, including his, became spaces where counter communities could thrive (The Blues Society).

While Nancy, Bill, and Robert knew of The Bitter Lemon, it was not their only stop in their search for the blues (The Blues Society). The documentary explains that they traveled to old neighborhoods collecting 78 rpm records to preserve the sound. They searched for musicians so they could create a concert for the blues, and here, performers could earn money for their music (The Blues Society). Thus, “The Memphis Blues Festival” was born.

The festival premiered on June 30, 1966, and The Blues Society spread the word (The Blues Society). According to Robert, in the film, the organizers of “The Memphis Blues Festival” sold ads about the event to local papers and used that revenue to purchase and print tickets to sell for admission. The preparation showed promise.

The second lesson I learned is that many counter communities in 1960s America lived fearfully in an unjust society. Just days before “The Memphis Blues Festival” premiered, the Ku Klux Klan held a rally in a neighboring park (The Blues Society). The threat of violence, however, did not stop the festival from happening (The Blues Society).

Footage of the festival in the documentary included rare film strips of Furry Lewis from 1966-1970. In addition, there are cuts in the film of Furry in later years in which he plays blues guitar with an accompanying guitarist Lee Becker. Lee says his job was to “make Furry Lewis sound good” (The Blues Society).

Watching scenes of an enthusiastic yet shy Rev. Robert Wilkins on stage (The Blues Society) in 1966 feels priceless. As he played the guitar and sang, his melody sometimes elongated the measures within the bars. These clips alone present a different take on the blues, one which might have been experienced by small communities in Memphis at the time.

Learning about the blues genre growing up, I understood that Chicago was the center for blues musicians. Producer, Arionne Nettles in a 2019 radio segment “How My Grandparents Helped Shape Chicago’s Blues Industry” which was part of WBEZ-91.5’s show “How Did The Great Migration Shape Chicago Blues?” writes in a synopsis of this clip, “In the 20th century, millions of black Americans who lived in southern states packed up and moved to northern cities – drawn by the promise of greater freedom and better jobs. Many headed to Chicago… They brought a musical genre that reflected the realities of black life: the blues” (Nettles, 2019). Further in the synopsis, she writes, “It was during this postwar period through the 1960s that Chicago was starting to create its own blues subgenre” (Nettles, 2019).

Dr. Palmer’s documentary supports Nettles’ story in the instance that many musicians who wanted careers did move from Memphis to Chicago to record. In a live Q&A at the Firehouse DCTV theater, where Dr. Palmer was interviewed by Rolling Stone Magazine critic, Anthony Curtis, Anthony asked her whether segregation was loosening up during this time (Curtis). Dr. Palmer said, “Not quite.” She also told Anthony that despite the threat of danger that segregation brought, when it came to defying authority, “they [The Blues Society] were foolish enough not to worry” (Palmer).

However, even with the deepest of convictions, the film explained that Robert still had struggled to contact blues musicians in Memphis. Joe Callicott, another guitarist who Robert sought to recruit for the festival, proved difficult to find (The Blues Society). The first time he tried to search for Joe, Robert got arrested and spent the night in jail (The Blues Society). Eventually, Robert did get Joe to perform on stage (The Blues Society).

More importantly, Dr. Palmer reassured Anthony and the audience that those musicians who performed at the “Memphis Blues Music Festival” got paid for their shows, making anywhere from hundreds to $1,000 (Palmer). Among these performers was Fred McDowell, the Mississippi-native guitarist who was recorded by archivist, Alan Lomax (The Blues Society). Another notable musician included Nathan Beauregard (The Blues Society), a blues guitarist whom according to an article by T. Dewayne Moore titled “Searching for Nathan Beauregard,” was believed to be the oldest performer there (Moore, 2020).

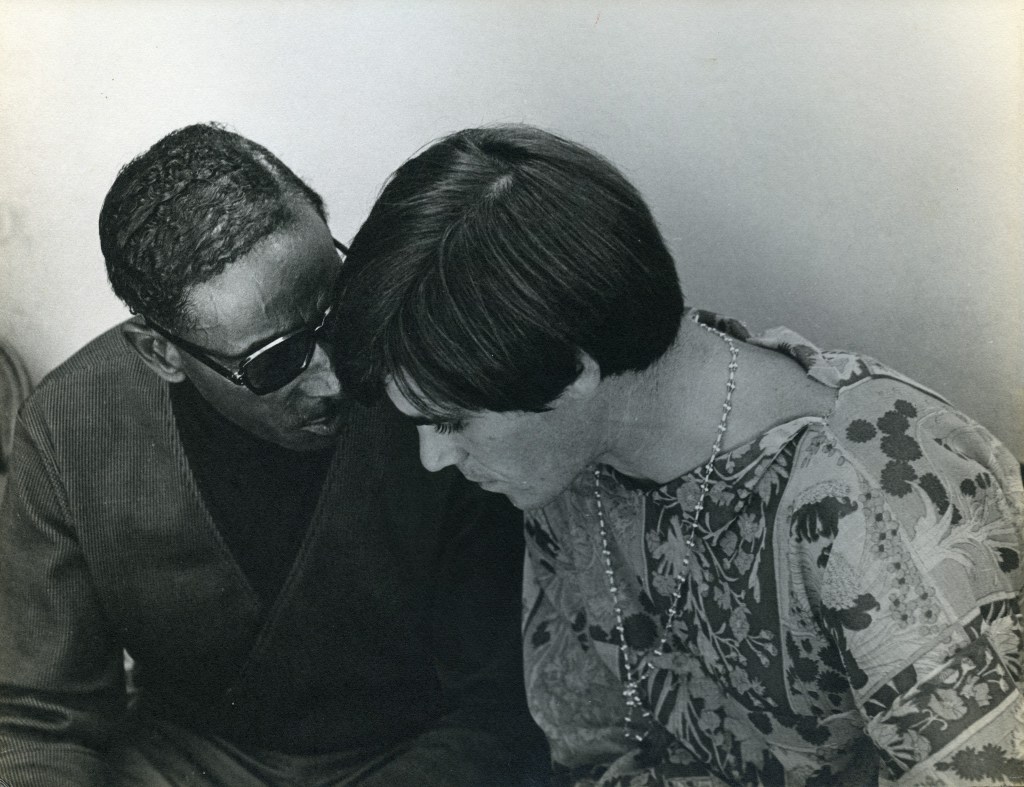

One clip within the film includes Bukka White playing guitar on stage at “The Blues Music Festival” underneath the hot sun. Nancy’s friend, Misty, joined Bukka on stage and held an open umbrella to shield him from the sun while he performed (The Blues Society). In the Q&A session, Dr. Palmer described this image as idyllic. In the documentary, however, Jamey expressed that she saw this as dangerous (Palmer).

The third lesson I learned is that while The Blues Society experienced success in bringing attention to the Memphis blues counter community, cultural appropriation overshadowed the origins of blues music.

Sociologist, Zandria Robinson, spoke in the documentary about American society at the time – more specifically, the battle of power dynamics. According to the King Institute, in 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated while standing outside on a balcony of his second-floor room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis (accessed June 29, 2024). In Dr. Palmer’s film, musician Dom Flemons mentioned how the rise of the Black Power movement in the 1970s encouraged young people to step away from the blues. Jamey follows up in a clip with a personal testimony of how she felt the need to “hate” the blues since it was seen as “lowly” (The Blues Society).

Further, Zandria describes the dangers of the growing cultural appropriation of the blues (The Blues Society). In the documentary, she says “Cultural appropriation is an obliteration.” One example in the film includes how Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of the UK-based rock band, Rolling Stones, took Rev. Robert Wilkins’ song “Prodigal Son” and played it on their record without giving Wilkins credit.

According to a Press Release from Baby Robot Media, this incident outraged The Blues Society. Thankfully, after Rolling Stone Magazine wrote an article about the situation, Rev. Wilkins would receive royalties for the song (Steven Albertson). However, in the Q&A session with Anthony, Dr. Palmer also mentioned that due to the large amount of collaboration, many writing credits were still not shared equitably with black musicians.

Jamey directly expressed in the film “The blues belongs to black Americans.”

The film also emphasizes that even during the peak of its success, specifically by 1969, when “The Blues Music Festival” had turned into a 3-day event, attracting new types of musical groups, like the blues and gospel-influenced soul group, The Bar-Kays, and Johnny Winter, many listeners started forgetting about the purpose of the event.

“The Memphis Blues Festival” was to benefit black musicians (The Blues Society). In footage which included Augusta’s mother, (and Robert’s wife at the time) Mary, taking the stage before Johnny Winter’s set, she clearly announces to the audience that she collected payment for only 800 tickets, when 3,000 people were attending the concert. “Why can’t you just pay for your tickets people?” Mary said urgently (The Blues Society).

From this moment, it did not take long for the film to jump to 2017, when The Blues Music Festival had its resurgence with Rev. John Wilkins, son of Rev. Robert Wilkins, as one of the acts (The Blues Society). Dr. Palmer told Anthony and the audience members that many black Memphians did show interest in the festival’s history during this resurgence. My only wish is that I would have seen more footage from this 2017 concert.

Watch The Blues Society? My recommendation and final thoughts

Now that I have told you all the lessons I have learned, do I think you should watch this documentary? Yes! Where can you watch it? The Blues Society, directed by Dr. Augusta Palmer has been released for rental or purchase on all major cable, satellite, and digital platforms.

Aside from the fact that this documentary challenged what I previously learned about the blues, I appreciate how Dr. Palmer does not shy away from addressing the impact of “The Blues Music Festival”, successes and failures. Anyone learning about music history in school, particularly about American music from the 1960s to the 1970s will benefit from watching this documentary.

The footage gathered is a nod to the past, helping us understand the need for music history and archiving. The Blues Society took this labor of love seriously in 1966, and the resurgence of the festival in 2017 proves the legacy that the founders wanted – to bring the blues to a public space. The resurgence brought back blues guitarist and singer, Rev. John Wilkins, whose father, Rev. Robert Wilkins, played in the festival fifty years prior.

Dr. Palmer interviewed Rev. John Wilkins and filmed him playing on stage, which would be one of his last shows before he passed away in 2020 from complications of the COVID-19 virus (The Blues Society). In the live Q&A session, Dr. Palmer told the audience that Rev. John’s legacy lives on with his daughters, who are part of a group called The Wilkins Sisters.

Although we have come a long way as an inclusive society since the ’60s, Augusta admits, “we still have a long way to go” (Steve Albertson). She says, “We all love the idea that music conquers all,” while also acknowledging that though “everyone can appreciate the blues music in this film, love for this music did not cure white supremacy, and white blues fans made part of a power structure that took advantage of black artists (Steve Albertson). I love the enthusiasm of that white hippy idealism, but the rules were much more stringent back then (Steve Albertson).”

While I appreciate other notable documentaries about the blues genre from the 1920s and beyond, highlighting specific musicians, such as Devil at the Crossroads: A Robert Johnson Story or What Happened, Miss Simone? – to name a couple –The Blues Society is a mixtape of various blues musicians in one film. Dr. Palmer’s film opens by telling viewers about a secret society of musicians in the late ‘60s who dedicated their lives to preserving the sound of the blues from Memphis but, the main stars of this film are the musicians who helped to build this genre.

Works Cited

Albertson, Steven. “Review: Music documentary The Blues Society playing select theaters and festivals leading up to its release to streaming on July 9-reevaluates the life of the Memphis Country Blues Festival through the lens of race, the counterculture of the ‘60s.” Baby Robot Media. 19 April 2024. Email to Patricia Trutescu.

“Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/assassination-martin-luther-king-jr . Accessed 29 June 2024.

The Blues Society. Directed by Augusta Palmer, Produced by Julia Tinneny, performance by Eric Roberts and Curtis Jackson. Cultural Animal 2024. Firehouse DCTV, New York, NY.

Moore, T. DeWayne. “Searching for Nathan Beauregard: Memphis Blues, Race, and the Myth of Southern Redemption Through a Love of Black Music.” T. DeWayne Moore. May 21, 2020. https://tdewaynemoore.com/snowball/searching-for-nathan-beauregard/?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTAAAR09rxmuoguRmxwenkIcIEYdDtwqLt-6o4KHT5UzuJkUUK6aUcONhMvhFsE_aem_OtfrfjVRMN5liWy9t5B1MQ Accessed 18 July 2024.

Nettles, Arionne. “How My Grandparents Helped Shape Chicago’s Blues Industry.” WBEZ Chicago. https://www.wbez.org/curious-city/2019/04/27/how-my-grandparents-helped-shape-chicagos-blues-industry. Accessed 29 June 2024.

Palmer, Augusta, Panelist. Interview. Moderated by Athony Curtis. “The Blues Society: Q&A,” 29 May 2024, Firehouse DCTV, New York, NY.

“I just want to keep putting out good work. To me, Miracles~Lost and Found is just one of many things I do. I am not downplaying it. I love the album. It’s not like that album where I am very performance art-y. Maybe some people think it is edgy and they hate it, or they believe that it is hip and cool; this for me, is a treat to say ‘This is an album for me to put on and hear a song, and then hear the next song.’ ”

“I just want to keep putting out good work. To me, Miracles~Lost and Found is just one of many things I do. I am not downplaying it. I love the album. It’s not like that album where I am very performance art-y. Maybe some people think it is edgy and they hate it, or they believe that it is hip and cool; this for me, is a treat to say ‘This is an album for me to put on and hear a song, and then hear the next song.’ ”